Maybe there’s a better way to start a conversation than to open with controversy, but since Buddhism draws its vitality from being a counter-culture movement, I’ll pick up on John Horgan’s brooding in Scientific American and take it apart a bit. He offers juicy points and sounds genuinely frustrated with a “spirituality” that he tried to embrace (four years of meditation before giving up ain’t nothing).

I confess Horgan pushed a button by arguing that Buddhism’s worldview cannot easily be reconciled with modern humanist values.

I also felt an overwhelming sense of life’s preciousness, but others may have very different reactions. Like an astronaut gazing at the earth through the window of his spacecraft, the mystic sees our existence against the backdrop of infinity and eternity. This perspective may not translate into compassion and empathy for others. Far from it. Human suffering and death may appear laughably trivial. Instead of becoming a saint-like Bodhisattva, brimming with love for all things, the mystic may become a sociopathic nihilist.

Wow! Modern humanist values themselves are under attack for being unfriendly to humans, so what exactly is Horgan talking about here?

But let’s not trifle … moving on ..

Buddhism and Catholicism

There’s plenty of irony to be found in Horgan’s equation of Buddhism with Catholicism. Plenty. First of all, we have to ask what “Buddhism” Horgan is referring to. My money is on Horgan having entered into Buddhism through Pureland. Many a lapsed Western Catholic, not atheist at all, has adopted Pureland, because it fulfills a need to “cling.” When it doesn’t meet the needs of the curious, they abandon it, because “secularists” are still struggling with the sense that belief in “something” is necessary in order to sustain humanity in a world constantly atilt. The “reenchantment” blah, blah, blah, movement is quietly present among second and third generation new agers here, to be sure.

While Horgan may find little difference between Buddhism and Catholicism, the Christian missionaries to East and South Asia responsible to shape Western early impressions of Buddhism certainly did.

The Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci encountered Chinese Buddhism in the early 1500s. Ricci thought it was idolatry and superstition – a false religion. He preferred Confucian scholars for their cultured minds, secular philosophy and advanced ideas on good government.

Only in Japan did Buddhism meet with Jesuit admiration. When Francis Xavier arrived in 1549 he challenged the Zen monks on doctrine. They laughed, saying Zen had no doctrine and no truths to transmit. At that point he figured the Jesuits were going to need God’s help to convert the Japanese. He wrote to the order asking for the most educated and capable missionaries that it could provide.

Personally, I doubt that Pureland offers a salvic goal compatible with Mahayana … if Mahayana is understood to be Śūnyatavāda at core. Over time I have come to actively dislike Pureland for its gross materialism, virtue ethics and surrender to some hierarchical figure who is nothing more than God in Heaven, Future Saviour or both. I think you just have to like chanting, and be so egocentric as to believe human words activate “primal” compassion (Tathāgatagarbha). Native Buddhists may not have such a luxury to disregard everything that Horgan chooses to identify as problematic with “Buddhism,” so the best that I can say about Pureland is that it casts the widest net as a possibly “comforting friend” across a lifetime of bitter suffering. I know good Pureland monks, and good Pureland believers, yet it is not hardly upright, active, nor demanding, nor rigorous enough of a practice for me.

Buddhism and Protestantism

Reverend Robert Spence Hardy (1803-1868) a Methodist missionary in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), was like Ricci. He ridiculed Buddhism as a parody of Christianity. For Ricci, the parody was demonic. For Hardy, it was merely uninspired.

Hardy was quite a collector. For our edification he brought back 465 works in Sanskrit, Pali, Sinhalese and Elu. His books, Eastern Monachism: An Account of the laws of the order of the order of the Mendicants (1850), the Manual of Buddhism in its Modern Development (1853), and The legends and theories of the Buddhists, compared with history and science (1866) elevated him as the central British authority on Theravada for over 30 years.

Nirvana was “extinction” and karma was “a singular law of production” that bound every being in its chain. Need I say that Horgan replicates these missionary frustrations?

Mysticism

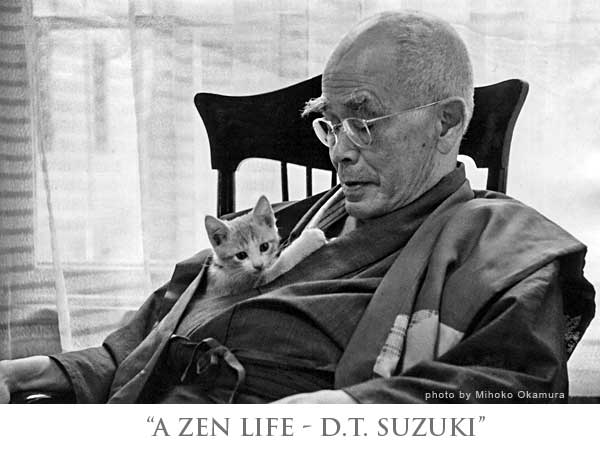

Suzuki was a Rinzai monk, a professor (at a Pureland university no less), a samurai and a Japanese nationalist. (None of these are dirty words.) He studied under Shaku Soen (釈 宗演 1860 – 1919), Japan’s delegate to the first World Parliament of Religions (1893 Chicago World Fair). Soen was the first Japanese to address the West on Japanese Buddhism and Suzuki was his interpreter.

Unlike Soen, Suzuki was fluent in English, and so, he ended up as the main Buddhist apologist to the West for over 60 years. He influenced the Theosophists, Alan Watts, the Beats, the Abstract Expressionists, John Cage, 1960’s counter-culture, deep ecology, steady state economics, and so much more. Then, looping back through Japan’s Kyoto School of philosophers (who Suzuki “Westernized”) he influenced of all people, Martin Heidegger.

Suzuki comes from a branch of Zen that emphasizes the use of koan as a means to dissolve the apriori, or mental content, as cognitive “ground.” Koans bring a practitioner to the point in which conceptual imputation is experienced as constructing, construction, constructed, or Empty (Śūnya) of essential content. We are deep in the territory of Immanuel Kant- deeper than Kant, because he believed that we have no choice but to rely upon rational categories, even though they are synthetic apriori. Buddhist Madhyamaka (Śūnyatavāda) did away with that, because believing in universals will lead you down the garden path. And thanks to Horgan, we have ample evidence of the garden path: Buddhist sociopathic “mystics” who don’t care about ethics and aren’t even Awakened, little own Enlightened, but believe themselves to be so. Yes, they definitely exist, just like Jesus freaks do.

Now, Japanese Rinzai is a demanding path that requires at least ten years of hard work toward conceptual dissolution. Suzuki advanced, specifically, Rinzai as the culmination of Buddhist thought. Moreoever, he was critical of the other main branch of Japanese Zen, Soto, with its emphasis on merely sitting, or shikantaza (只管打坐). To make a cognitive bridge he likened Rinzai’s dynamic “peak experiences” to Western mystical ones. It is a cliché in the West to describe Zen Enlightenment as realized in “sudden illuminations” (kenshō 見性), but such descriptions are hardly native to Rinzai, or Buddhism. In America, the Emersonian Transcendentalists, already, under the influence of the Kantian sublime, had built this bridge backward to “mystical experience,” through the Indian Upaniṣads. It is only fairly recently, in the work of Bernard Faure for instance, that Suzuki’s apology has been identified for what it is, and corrections to his presentation, at a very high level, have been advanced.

So let’s understand. By the time Suzuki arrived in the West (which was pretty early in terms of our knowledge of Buddhism) an interpretive ground had been prepared for him that eased his description of “Buddhist” truth as not merely ineffable, but as transcendental. Which “Buddhist” truth is not. This I will demonstrate, and such demonstration is a big object of study of mine. Understanding comes through hard work, it is immanent and affects mundane existence.

No Self

Horgan suggests that Buddhist explanations of non-self do not respond to philosophical explanations of “emergent” phenomenon.

“Where, exactly, is your self?” Buddha asked. “Of what components and properties does your self consist?” Since no answer to these questions suffices, the self must be in some sense illusory. …..

Not really. There is a conventional self in Buddhism that is described as an aggregation of five heaps (khandhās). The early Buddhist sutta insist that self-identity and suffering emerge with “clinging” to the Five Aggregates. The famous Twelve-Linked Chain of Causation describes this very “emergence” of Self as a syndrome, this heap of suffering that is the human condition.

…… Actually, modern science – and meditative introspection – have merely discovered that the self is an emergent phenomenon, difficult to explain in terms of its parts.

Yes, Buddhist teachers do critique rationalists for not being able to land on anything “real” (a little word with big meanings) like a soul. However, as we all know, good luck with scientific proof for Self as existent or non-existent either way, John.

The Buddhist argument is that phenomena arise co-dependently, in conjunction with any number of contributing factors, and, especially, in conjunction with the working of our minds. All sensory experiences pass and, therefore, are transient. Continuity, on the other hand, is wholly constructed; it does not simply emerge. Again we find ourselves in Kantian territory: skepticism over self-caused phenomena that can be said to truly exist “outside” our perception of them.

Horgan’s Stevens Institute is there, but, as he admits himself, it’s hard to pin down as a singular phenomenon. As well, many assumptions have to be in place in order for us to recognize it. So many, in fact, that we forget ever having put them in place. Do you remember developing a concept of space? Out of what? Kant, for instance, argues that the only ground you have by which to develop a conceptual understanding of space is experience. Since, you can never experience the entirety of space (it is a whole), you can only form a conceptual “slice” of what it may be. Time is an even more elusive phenomenon.

Now, on the question of knowing that something exists, Zen (Mahayana) Tibetan Buddhism (Mantrayana) and Theravada (Abhidharma) all have different points of view. The whole conversation will have to wait for another day, but what needs to be said is that Horgen mistakenly equates Tibetan Buddhism with Zen.

There is no doubt tantra and Zen share common interests, but according to Zen, knowing that something exists can be grasped by anyone; expressing its existence “completely” is beyond our reach. Something is obviously not transcendental if we experience it. Tantra, on the other hand, holds that “perfected wisdom” can be communicated through signs, but the experience is participatory and for the initiate only. Tantra tends toward the transcendental. Not all Tibetan Buddhist schools are the same, however, some are close to Hinduism (which is transcendental) while others cleave to Śūnyatā metaphysics.

Rationalism

Western modernity is hegemonic, so it is no surprise that all Buddhist apologists have found themselves up against it, seeking acceptance from Westerners in every way. Anagārika Dharmapāla (1864-1933) Ceylon’s representative at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893, tried to appeal to Western thinking in a different way than Soen and Suzuki. This is the guy who emptied Buddhism of its supernatural elements and made it a rational, individualist way of life, good for the mind, good for society.

Like Suzuki, Dharmapala was fluent in English and able to show that Buddhism was a logical system compatible with ‘modern’ ideas. He attacked the Social Darwinist proposition that spiritual evolution was supposed to result in a type of universal rational Christianity. Specifically, he opposed the view that Buddhism represented an early stage in the historical progression of spirituality from East to West, and demonstrated that Buddhism had its own theory of evolution, which had developed roughly 2500 years before Darwin appeared on the scene. In this way – though it took much doing – he and his Theravada successors were able to bring Buddhism to the fore as a humanist tradition able to respond to modern “scientifically informed” spiritual and philosophical problems. Horgan is undoubtedly attacking Theravada claims to rationalism. Again, this must be addressed later.

Karma

First of all, reincarnation is not a word to apply to Buddhist beliefs about karma and rebirth. The notion of a reincarnating soul (purusa, jiva, atman) possibly emerged within India’s Samkya school of philosophy. It is a Jain and Hindu concept, not a Buddhist one, and it definitely goes back to the Rgveda. Secondly karma, as we all should know, collects “doing” with the “making” of consequences. It’s causal theory. I do not assume pre-Buddhist beliefs in a cosmic moral law (such as the Vedic rta, Chinese Tien), go unchallenged in Buddhist cultures, simply because they intermingle with other more Buddhist ones. Without getting into complex ideas about how nirvana is the cessation of discursive production (i.e karma), let me say this, according to Buddhist thought, the morality of an act is found in the intentions behind it. So really, if Horgan doesn’t feel himself to be suffering, no good Buddhist would want him to.