Vedāḥ refers the sacred knowledge held in four ancient Indian collections (saṃhitās): the Ṛgvedāḥ, the Sāmavedāḥ, the Yajurvedāḥ and the Atharvavedāḥ.

Indians revere the Vedāḥ as holy. According to the Pūrva-Mīmāṃsā (300-200 BCE) school (darśana), the ancient poets (ṛṣis) acquired sacred knowledge through mystical experience as hearers (śrotṛ) and seers (draṣṭā). They called it śruti (heard) or dṛṣṭi (seen). It is eternal revelation not-of-man (apauruṣeya), self-evident (svataḥpramāṇa), perfect, infallible and all-knowing (viśvavid).

Dating the Vedāḥ remains “ten pins set up to be bowled down,” but the Ṛgvedāḥ is our oldest extant Indo-Iranian literature. As well, a prehistoric, Atharvanic religion existed alongside the Ṛgvedāḥ, so the Atharvavedāḥ is considered very old.

The Atharvavedāḥ is a book of magical incantation. It goes by two other titles: the Ātharvāṅgirasaḥ (AV X:7.20) and the Bhṛgu–AṅgirasaḥSamhita (Bhārgavavedāḥ). It stands apart from the three-fold (trayī) Ṛg, Sāma and Yajur vedās which form an interlocking system of śrauta rites. The Atharvavedāḥ was compiled later, and only became recognized as part of the Vedāḥ some time before the first millennium CE.

Each vedāḥ developed around a saṃhitā, which is a collection of hymn (uktha), chant (udgītha) or mantra, and preserved by different schools (śākhās). At one time there were many recensions. While only a small number survive, they cover a vast body of works.

Except for the Atharvavedāḥ, which has no Āraṇyaka (Forest Book), each vedāḥ contains at least one Brāhmaṇa (Ritual Book), one Āraṇyaka (Forest Book) and one Upaniṣad (Book of Secrets).

The Āpastamba Śrautasūtra (c. 400 BCE) divides the Vedāḥ into two groups (kāṇḍa): Karmakāṇḍa (Ritual Books) and Jñānakāṇḍa (Knowledge Books). The Karmakāṇḍa is the Saṃhitā and Brāhmaṇa: the utterances of poet (ṛṣi) and priest (brāhmaṇa). The Jñānakāṇḍa is the Āraṇyaka and Upaniṣads: the utterances of philosopher (ācārya) and student (brahmacārin).

The one sits, blooming a blooming of verses, the other sings a song in śakvarī verses. The one, the formulator, speaks the knowledge born, and the other measures out the measure of the sacrifice.

Br̥haspati Āṅgirasa (RV X.71)

The Vedāḥ are also identified according to their priests (rtvij, vipraḥ).

- The Ṛgvedāḥ is the preserve of the Hotṛ, the liturgist who chants the right hymn (sūktam) at the right time to invoke the gods and make their bond.

- The Sāmavedāḥ is the song book of the Udgātṛ, the long-haired chanter (vedavaktāra) of melody (sāman) descended from celestial musicians (Ghandarvas).

- The Yajurvedāḥ is the prayer book of the Adhvaryu, the ritualist responsible for carrying out rites (yaju) and who distributes soma.

- The Atharvavedāḥ is the preserve of the Brahmān, the head priest who silently sits south of the sacrifice (yajña) and rectifies any mistakes.

Karmakāṇḍa

In the saṃhitās, the term karman (work) refers to the ritual toil of sacrifice (yajña) that produces whatever is desired. Thus, the karmakāṇḍa contains the tools that the sacrificial priests (ṛtvij) used to carry out śrauta rites.

Saṃhitā

A saṃhitā is a collection of sacred utterances, verse (ṛc) or formula (mantrāṇām), that are hymned, chanted or muttered during the ritual. These are euphonically fused together according to set rules of combination (sandhi).

Ṛgvedāḥ (ऋग्वेद)

The Ṛgvedāḥ Saṃhitā is very old and contains archaic, not merely ancient, verse. It is the core of the trayīvidya (Ṛg, Sāma,Yajur), which the Buddha also knew. Its poets (ṛṣis) were fascinated with the cosmos, patterns in nature, forces in nature, elemental mysteries and the source of poetic divination itself.

We have only one Ṛgvedāḥ available to us: the well preserved Śākala Śākhā (500 BCE). It arranges the sūktam in ten Maṇḍala (round, ring) of uneven size.

Western scholars tend think the sūktams were gathered into collections 1500 – 1200 BCE and leave dating their composition an open question. In Indian tradition, the Viṣṇu Purāṇa (300 BCE – 500 CE) states that the Ṛgvedāḥ‘s earliest sūktam were composed in the age of truth (Satya Yuga), before 3500 BCE.

Altogether the Saṃhitā contains 1028 lyric poems (sūktam) or ‘bright statements’ composed by over 400 ṛṣis in precise metrical verse (ṛc). In total that is 10,552 verses (ṛc). Hence its name: ṛcvedāḥ. Most ṛc are assigned a poet (ṛṣi), a god (devatā) and a metre. The most famous lyric metre is the Gāyatrī, (of the famous Gāyatrī mantra, which even Buddha knew). It contains three lines of eight syllables each.

The Saṃhitā names at least three generations of Ṛgvedāḥ poets (ṛṣis). Each belongs to a clan (gotra) that traces its lineage back to a root clan (mulagotra) of even older generations going back to four distant ancestors: Atharvā (अथर्वा), Aṅgirā (अङ्गिरा), Bhṛgu (भृगु), and Trita Āptya (त्रित आप्त्य) or Vasistha.

The hymns (uktha) of the Aṅgirases dominate and nearly 80 per cent of all hymns (uktha) are dedicated to one god (devatā), Indra. Mostly, the Ṛgvedāḥ poems (sūktam) are liturgical and display a high level of convention. Nonetheless, the poets (ṛṣis) pressed upon ritual convention with skill and subtlety. The Ṛgvedāḥ‘s ancient poetry (kāvya) is well-governed, finely crafted of the highest quality. As well, it deploys ingenious poetic devices that were carried down through the Upaniṣads into Classical Sanksrit poetry (kāvya), such as the Rāmāyaṇa and Kālidāsa’s Meghaduta.

Atharvavedāḥ (अथर्ववेद)

The Atharvavedāḥ Saṃhitā is considered the second oldest vedāḥ, mainly because its free lyric and metre is most like the Ṛgvedāḥ. It contains over 700 lyrical poems (sūktam), of which about one-sixth are found in the Ṛgvedāḥ. There are two extant recensions (śākhās), the Paippalāda Śākhā, which is the older of the two, and the widely used Śaunakīya Śākhā.

The Atharvavedāḥ is attributed to the Atharvā and Aṅgirā poets (ṛṣis). Both clans are revered path makers (pathikṛt) of antiquity. According to the Nirukta of Yāska, an ancient etymology of vedic terms, Atharvā means yogi and cure (bheṣāja). Aṅgirā is a form of the god of fire (Agni), and it means messenger. Aṅgāra means burning coal or ash.

He has attained attainments, he has attained the strong hold of the living, for a hundred physicians are his, also a thousand plants.

Atharvavedāḥ (II.9.3)

The Atharvavedāḥ is a medical (bheṣāja) manual that includes descriptions of anatomy, surgical techniques, thoughts on causes of some diseases (yakṣma), primitive therapies, the use of local herbs, plants, minerals — and the spells and amulets (ātharvaṇaḥ) that make these cures work.

Not surprisingly, there is much continuity between the Atharvavedāḥ and Ayurveda. The Atharvāṇas and Bhārgava poets (ṛṣis) were physicians par excellence. They knew the medicines, prepared the cure, therapy, the amulets and the healing rituals. As such, they were formidable, and retaining them was a sign of wealth and prosperity.

The Atharvavedāḥ also records popular beliefs, such as that it is demons (rākṣasa), or an enemy’s evil eye, and especially the malignant goddess Nirṛti, who inflict diseases. It contains a demonology, along with magical fire charms (āṅgirasaḥ), and curses to ward off evil, or even to plague an enemy oneself.

Sāmavedāḥ (सामवेद)

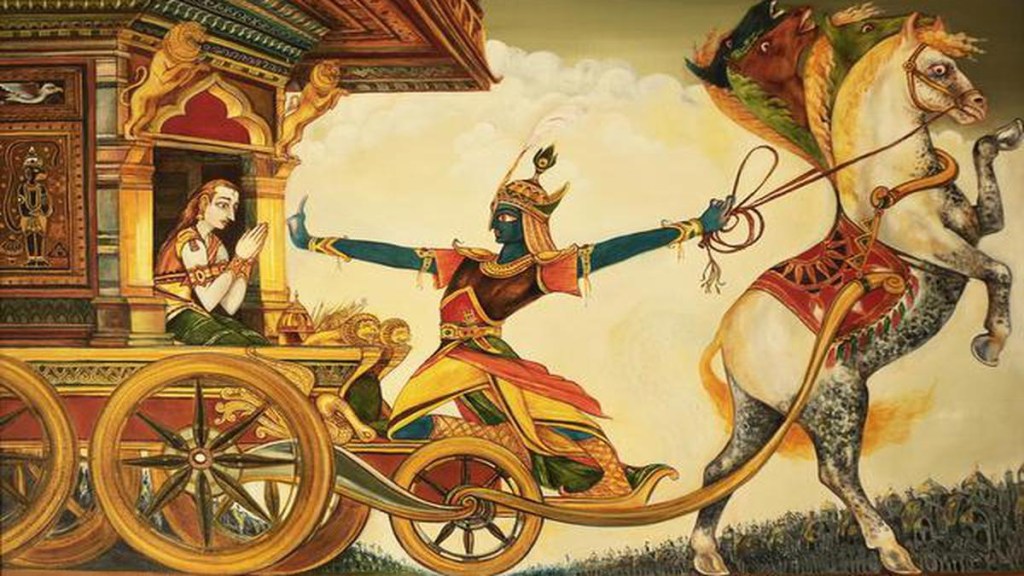

The Sāmavedāḥ Saṃhitā focuses on chants. Some of its melodies (sāman) are ancient, and two are mentioned in the Ṛgvedāḥ (e.g., Rathantara). It is the shortest vedāḥ, but in India it is foremost, because it is enchantingly sung. In the Bhagavad Gita, Kṛṣṇa declares himself to be the Sāmavedāḥ.

I am the Sāmavedāḥ among the Vedāḥ and Indra among the gods. I am the mind among the senses; I am consciousness among living beings.

Śrīmadbhagavadgītā, (10.22)

There are three extant Sāmavedāḥ śākhās: the Jaiminīya (Talavakāra) Saṃhitā, which is the oldest, the Kauthuma Saṃhitā, which is the best known, and the Rāṇāyanīya Saṃhitā, which is a Kauthuma sub-school.

The Kauthuma Śākhā Saṃhitā contains 1875 verses (ṛc), of which 1771 were torn from Ṛgvedāḥ. They were rearranged, modified euphonically and set to melodies (sāman). This reorganization of the verses (ṛcs) so disrupted their language that they are almost without any internal connection, save to indicate the gods (devatā) who are enjoined in the sacrifice. These modified ṛcs are called mantrā (formulas).

Yajurvedāḥ (यजुर्वेद)

The Yajurvedāḥ is different from the Ṛgvedāḥ and Sāmavedāḥ. It emphasizes ritual praxis (śrāddha) and is written in a prose style that became characteristic of the later Brāhmaṇas. Like the Brāhmaṇas, it is dominated by the need for ritual purity and perfection.

It is a sprawling thing that contains two semi-parallel streams of vedāḥ: the Black Yajurvedāḥ (Kṛṣṇayajurvedāḥ) and the White Yajurvedāḥ (Śuklayajurvedāḥ). The older Black Yajurvedāḥ Saṃhitā contains mantrā “muddled” with prose exegesis. The White Yajurvedāḥ Saṃhitā contains only mantrā, thought to have been lifted from a saṃhitā like the Black Yajurvedāḥ that is much older than any of the extant Śuklayajurvedāḥ recensions (śākhās).

Most of the Yajurvedāḥ‘s 2086 verses (ṛc) were torn from the Ṛgvedāḥ, chopped up and rearranged to become mantrā. The mantrā are woven into rituals (yajus). Yajus are words, formulas, prescriptions and passages, some in connected form (sandhi), that link ritual action to verse (ṛc). The mantrā must be muttered at the right time and place, whether during ritual (yaju) or at more practical times (e.g., as curses).

The Kṛṣṇayajurvedāḥ has four extant recensions (śākhās): the Taittiriya Śākhā of south India, which is best known, the Maitrayani Śākhā, which is the oldest, the Kathaka Śākhā of Kashmir and Kapishthala Śākhās, of which only parts are extant.

The Śuklayajurvedāḥ has two surviving śākhās: the Madhyamdina Śākhā and Kanva Śākhā. The Kanva Śākhā is geographically associated with the ancient kingdom (mahājanapada) of Kosala, home territory of the Buddha and land of the sky walker (muniḥ) who has gone forth (pravrajiṣyan) into asceticism (tāpas).

Brāhmaṇa

Sacrificial practice constitutes the main religion of the Brāhamaṇas, which is quite simple: the gods long for oblations, priests long for sacrificial fees and the sacrificer (host) longs to obtain power, prosperity, immortality and bliss through the sacrifice. Rebirth beliefs appear.

The Brāhmaṇas record a “floating mass of intricate discourses” on hundreds of śrauta rites that developed within a priestly institution (brāhmaṇa) which performed and controlled the sacrifice.

The śrauta rites are based on the śruti (what was heard), so many priests (brāhmaṇa) belonged to the clans of the Ṛgvedāḥ poets (ṛṣi). They debated (vā́jina) with each other over ritual matters, such as the rituals’ origin, meaning, conduct and validity in relation to the sacrifice. As well as what was the sacrifice?

The Brāhmaṇas do not offer step-by-step ritual procedures. They presuppose familiarity with all aspects of the rites and their patterns. Rather, they discuss exegetical myths (itihāsa) and rules (vidhi), e.g., “silver is not a suitable gift, for it has arisen from tears,” and deliberate over meaning (arthavāda) and precedents (parakrti). As well, they speculate on cosmology and apply astronomy and geometry, especially in relation to construction of ritual tools such as the fire altar. They carry out polemics, debate fine points and fix minute details.

Some material was composed on the sacrificial ground during a “dry run” for students.

The priests’ (brāhmaṇa) complete, perfect knowledge of the intricacies of ritual praxis (śrāddha) becomes crucial and their focus on techne shifts ritual attention away from the gods (devatā) toward the body of the sacrificer (ātman), whether host or priest. This shift led to such concepts as prāṇā (life force) and manas (transcendental mind).

Notably, the Brāhmaṇas re-envision the sacrifice as the primordial (adhiyajña) cosmos, overseen by the god Prajāpati (Lord of Creatures), the divine fount of the manifold. They higlight correspondences between cosmos, sacrifice, rite and sacrificer to conceptually unify the divine cosmos and sacrificer’s body (ātman) into one conditioned space (ātman).

Thus, they justify the śrauta rites as an essential connection between priest, man and cosmos in a cyclical whole, and emphasize that both humans and gods must sacrifice to keep the wheel of creation turning.

The oldest Brāhmaṇa is the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa. The best known is the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa.

- Ṛgvedāḥ: Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, Kauṣītaki Brāhmaṇa

- Atharvavedāḥ: Gopatha Brāhmaṇa

- Sāmavedāḥ: Tandya Mahabrāhmaṇa (or Panchavimsa Brāhmaṇa), Jaiminīya (or Talavakāra) Upaniṣad Brāhmaņa

- Kṛṣṇayajurvedāḥ: Taittiriya Brāhmaṇa

- Śuklayajurvedāḥ: Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa

Jñānakāṇḍa

Jñāna (knowledge), refers to the inner vision of the Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas. Roughly, the jñānakāṇḍa is the forest books (Aryanka), which are an extension of the Brāhmaṇas, and their books of secrets (Upaniṣads). Brāhmaṇa, Āraṇyaka and Upaniṣad are often blurred and some Brāhmaṇas are practically indistinguishable from their Āraṇyaka and Upaniṣad.

Āraṇyaka

The Āraṇyakas share the Brāhmaṇas‘ prose style and can usually found at their end. They are filled with esoteric contemplations on the sacrifice (yajña), rather than concerns over ritual perfection. Their topics are knowledge of creation (Prajāpati or Brahmā), the awakening of self (brahmavidyā), vital breath (prāṇavidyā) and how to approach the divine (upāsanā).

They cover a mediate sphere of devotion (bhaktimārga), or personal relation with the divine, between the ritual path of the Brāhmaṇas (kārmamārga) and the wisdom path of the Upaniṣads (jñānamārga).

Āraṇyaka means “belonging to the forest” (araṇya). At the time of the Āraṇyakas, the forest may have been connected powerful ideas that were too dangerous to be taught in the village. The texts present a tradition (vānaprastha) in which a brāhmaṇa sage (ācārya) and student (brahmacārin) head into the secluded forest for discussion and teaching.

This tradition (vānaprastha) likely expresses early development of the rite of “taking near” (upanayana). In the upanayana, a sage (ācārya) initiates his student (brahmacārin) into the privileged status of the twice-born (dvijā) who know the self (ātman) dwelling in Brahmā’s heaven (brahmaloka).

The extant Āraṇyakas are as follows:

- Ṛgvedāḥ: Aitareya Āraṇyaka, Kauṣītaki Āraṇyaka

- Atharvavedāḥ does not contain an Āraṇyaka

- Sāmavedāḥ: Talavakāra Āraṇyaka

- Kṛṣṇayajurvedāḥ: Taittiriya Āraṇyaka, Maitrayani Āraṇyaka, and Kaṭha Āraṇyaka

- Śuklayajurvedāḥ: Bṛhadāraṇyaka Āraṇyaka

The Aitareya and Kauṣitaki Āraṇyakas treat the Great Vow (Mahāvrata) Rite (winter solstice). The Bṛhadāraṇyaka of the White Śuklayajurvedāḥ treats the Pravargya rite (offering of heated milk and ghee to the Aśvins).

Upaniṣad

The Upaniṣads are called the end of the Vedāḥ (Vedānta). They claim shared authorship with the Brāhmaṇas and are connected to them via the Āraṇyakas. The primary relationship in the Upaniṣads is between the sage (ācārya) and student (brahmacāri). Their metaphysical speculation and use of various contemplative disciplines form the foundation for Hindu theosophy.

In the Brāhmaṇas, the term ‘upaniṣad‘ refers to the original cause of something else. Not surprisingly, the Upaniṣads quest for first cause in their approach to the divine (upāsanā). They are preoccupied with the secret (rahasyam) of the Vedāḥ. The hidden connections (bandhu: बन्धु) highlit by the Brāhmaṇas undergo transformations that reveal the true reality of ātman (self). It is the imperishable immensity of Brahmā, or brahman. The classical Upaniṣadic expression for the experience of brahman is saccidānanda, the true bliss of spirit.

The Upaniṣads‘ micro-macrocosmic vision of ātman–brahman includes the idea that humans are fettered by ignorance (avidyā) and desire (kāma), which produces a dissatisfying existence. Knowledge (vidyā) is the path that leads to release (mokṣā) from the ritual cycle of creation (samsara).

As the spider moves along its thread, or as from a fire tiny sparks fly in all directions, even so from this ātman come forth all vital forces, all worlds, all gods, all beings. Its secret name is “the Truth of truth.” Breath is truth and its truth is ātman.

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (II.i.20)

In Indian tradition, there are thirteen principal (mukhya) Upaniṣads. The most recent to gain scholarly attention are the Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad and Praśnopaniṣad of the Atharvavedāḥ.

So far, Buddhists have been most attracted to the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad. It records the first renunciation (saṃnyāsa) of a brāhmaṇa, Yajnavalkya, who goes forth (pravrajiṣyan) into asceticism (tāpas).

- Ṛgvedāḥ: Aitareyopaniṣad, Kauṣītaki Upaniṣad, Nirvāṇopaniṣad, Nādabindu Upaniṣad, Akṣamālika Upaniṣad, Ātmabodhopaniṣad, Bahvṛca Upaniṣad, Mudgala Upaniṣad, Saubhagyalakshmyupanishad, Tripurā Upaniṣad

- Atharvavedāḥ: Praśnopaniṣad, Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad, Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad

- Sāmavedāḥ: Chāndogyopaniṣad, Kenopaniṣat, Vajrasūcī Upaniṣad, Mahā Upaniṣad, Sāvitrī Upaniṣad, Āruṇeya Upaniṣad, Maitreya Upaniṣad, Brhat-Sannyāsa Upaniṣad, Kuṇḍika (or Laghu-Sannyāsa) Upaniṣad, Vāsudeva Upaniṣad, Avyakta Upaniṣad, Rudrākṣa Upaniṣad, Jābāli Upaniṣad, Yogachūḍāmaṇi Upaniṣad, Darśana Upaniṣad

- Kṛṣṇayajurvedāḥ: Taittiriya Upaniṣad, Śvetāśvataropaniṣad, Kaṭhopaniṣad, Maitrāyaṇīya Upaniṣad, Brahma Upaniṣad

- Śuklayajurvedāḥ: Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, Īśopaniṣad